Designing a Tiny URL

- Designing a Tiny URL

Designing a Tiny URL

1. What is Tiny URL?

Shortened URL shuld be random and unique. It should be a combination of characters (A-Z, a-z) and numbers (0-9).

TinyURL is a web based service which - </br>

- Takes a long URL and creates a shorter URL

- Takes short URL and redirects the user to the original Long URL

2. Why do we need URL shortening?

Short links save a lot of space when displayed, printed, messaged, or tweeted. Additionally, users are less likely to mistype shorter URLs.

For example, if we shorten this page through TinyURL:

- https://zhengstar94.github.io/#/md/AlgorithmReview/Array/TwoNumberSum

we would get:

- http://tinyurl.com/kmh7aqd

- The shortened URL is nearly one-third the size of the actual URL.

- URL shortening is used for optimizing links across devices, tracking individual links to analyze audience and campaign performance, and hiding affiliated original URLs.

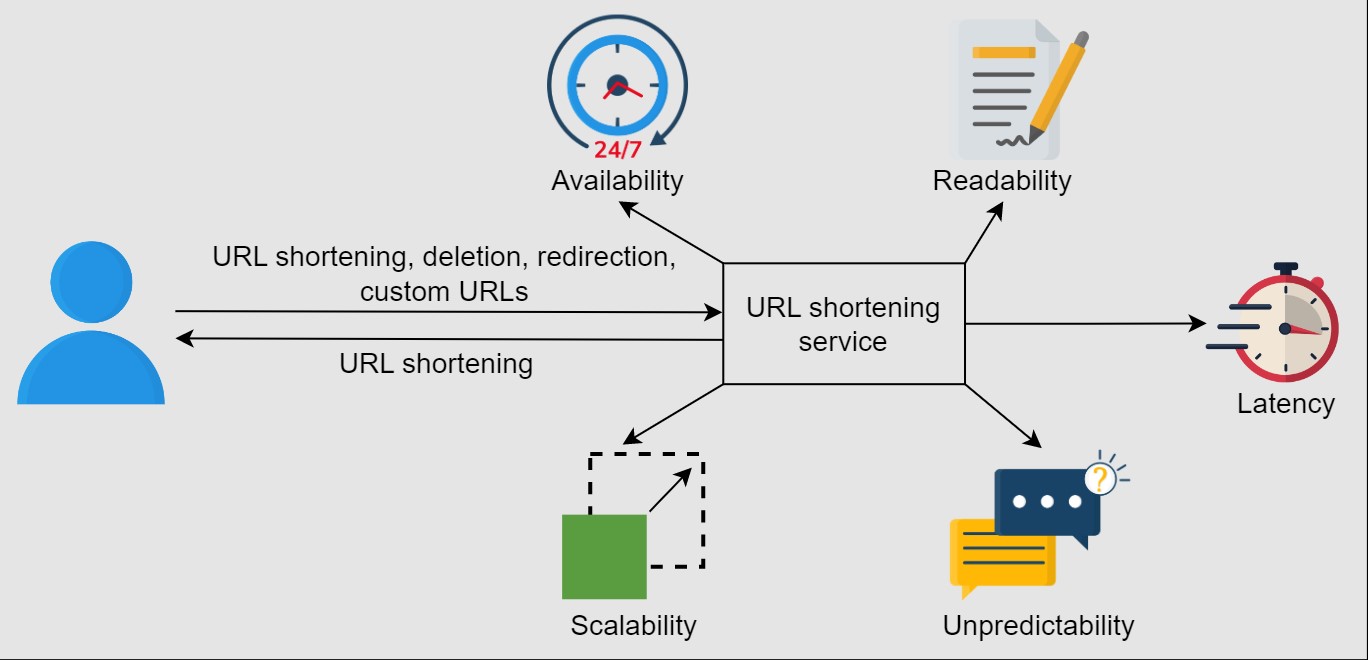

3. Requirements for URL Shortening Design

3.1 Functional Requirements:

- Short URL generation: Our service should be able to generate a unqiue shorter to the original URL.

- Redirection: Given a short link, our system should be able to redirect the user to the original URL.

- Custom short links: Users should be able to generate custom short links for their URLs using our system.

- Deletion: Users should be able to delete a short link generated by our system, given the rights.

- Update: Users should be able to update the long URL associated with the short link, given the proper rights.

- Expiry time: There must be a default expiration time for the short links, but users should be able to set the expiration time based on their requirements.

Question

As a design choice, we don’t reuse the expired short URLs. Since we don’t reuse them, why do we need to delete them from our system?

Answer

So far, we’ve kept the default expiration time to five years. If we relax that limitation and start saving the records forever, our datastore’s search index will grow without bound, and querying time from it can add noticeable latency.

3.2 Non-Functional Requirements:

- Availability: Our system should be highly available, because even a fraction of the second downtime would result in URL redirection failures. Since our system’s domain is in URLs, we don’t have the leverage of downtime, and our design must have fault-tolerance conditions instilled in it.

- Scalability: Our system should be horizontally scalable with increasing demand.

- Readability: The short links generated by our system should be easily readable, distinguishable, and typeable.

- Latency: The system should perform at low latency to provide the user with a smooth experience.

- Unpredictability: From a security standpoint, the short links generated by our system should be highly unpredictable. This ensures that the next-in-line short URL is not serially produced, eliminating the possibility of someone guessing all the short URLs that our system has ever produced or will produce.

Question

Why is producing unpredictable short URLs mandatory for our system?

Answer

- Attackers can have access to the system-level information of the short URLs’ total count, giving them a defined range to plan out their attacks. This type of internal information shouldn’t be available outside the system.

- Our users might have used our service for generating short URLs for secret URLs. With the information above, the attackers can try to list all the short URLs, access them and gain insights about the associated long URLs, risking the secrecy of the private URLs. It will compromise the privacy of a user’s data, making our system less secure.

Hence, randomly assigning unique IDs deprives the attackers of such system insights, which are needed for enumerating and compromising the user’s private data.

3.3 Resource estimation

Assumptions

- We assume that the shortening:redirection request ratio is 1:100.

- There are 200 million new URL shortening requests per month.

- A URL shortening entry requires 500 Bytes of database storage.

- Each entry will have a maximum of five years of expiry time, unless explicitly deleted.

- There are 100 million Daily Active Users (DAU).

3.4 Storage estimation

Since entries are saved for a time period of 5 years and there are a total of 200 million entries per month, the total entries will be approximately 12 billion.

200 Million/month×12 months/year×5 years=12 Billion URL shortening requests

Since each entry is 500 Bytes, the total storage estimate would be 6 TB: 12 Billion×500 Bytes=6 TB

URL Shortening Service Storage Estimation Calculator

URL shortening per month 200 Million

Expiration time 5 Years

URL object size 500 Bytes

Total number of requests 12 Billion

Total storage 6 TB

3.5 Query rate estimation

Based on the estimations above, we can expect 20 billion redirection requests per month.

200 Million×100=20 Billion

We can extend our calculations for Queries Per Second (QPS) for our system from this baseline. The number of seconds in one month, given the average number of days per month is 30.42:

30.42 days×24 hours×60 minutes×60 seconds=2628288 seconds

Considering the calculation above, new URL shortening requests per second will be:

200 Million/2628288 seconds = 76 URLs/s

With a 1:100 shortening to redirecting ratio, the URL redirection rate per second will be:

100×76 URLs/s=7.6 K URLs/s

3.6 Memory estimation

We need memory estimates in case we want to cache some of the frequently accessed URL redirection requests. Let’s assume a split of 80-20 in the incoming requests. 20 percent of redirection requests generate 80 percent of the traffic.

Since the redirection requests per second are 7.6 K, the total would be 0.66 billion for one day.

7.6 K×3600 seconds×24 hours=0.66 billion

Since we would only consider caching 20 percent of these per-day redirection requests, the total memory requirements estimate would be 66 GB.

0.2×0.66 Billion×500 Bytes=66 GB

URL Shortening Service Estimates Calculator

URL shortening per month 200 Million

URL redirection per month 20 Billion

Query rate for URL shortening 76 URLs / s

Query rate for URL redirection 7600 URLs / s

Single entry storage size 500 Bytes

Incoming data 304 Kbps

Outgoing data 30.4 Mbps

Cache memory 66 GB

3.7 Number of servers estimation

We adopt the same approximation discussed in the back-of-the-envelope calculations to calculate the number of servers needed: the number of daily active users and the daily user handling limit of a server are the two main factors in depicting the total number of servers required. According to the approximation, we need to divide the Daily Active Users (DAU) by 8000 to calculate the approximated number of servers.

Number of servers = DAU/8000 = 100 M/8000 = 12500 servers

3.8 Summarizing estimation

Based on the assumption above, the following table summarizes our estimations:

Type of operation Time estimates

New URLs 76/s

URL redirections 7.6 K/s

Incoming data 304 Kbps

Outgoing data 30.4 Mbps

Storage for 5 years 6 TB

Memory for cache 66 GB

Servers 12500

4. High Level Design

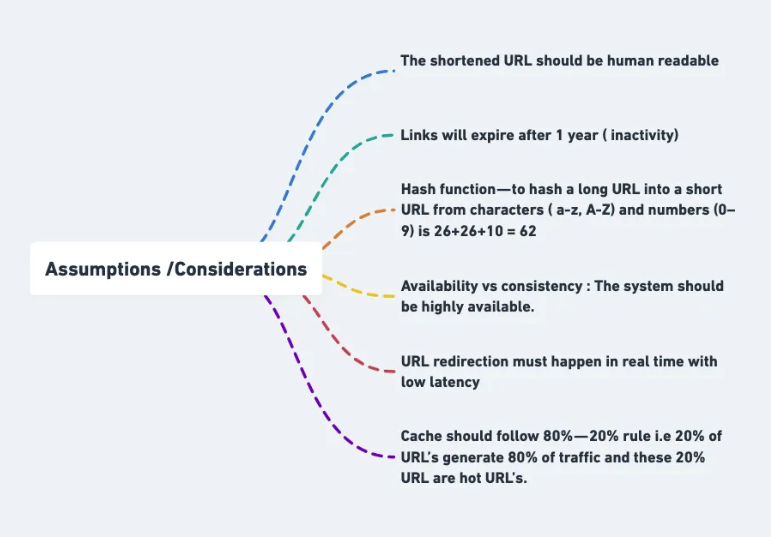

Assumptions / Considerations

- The shortened URL should be human readable

- Links will expire after 1 year ( inactivity)

- Hash function — to hash a long URL into a short URL from characters ( a-z, A-Z) and numbers (0–9) is 26+26+10 = 62

- Availability vs consistency : The system should be highly available.

- URL redirection must happen in real time with low latency

- Cache should follow 80% — 20% rule i.e 20% of URL’s generate 80% of traffic and these 20% URL are hot URL’s.

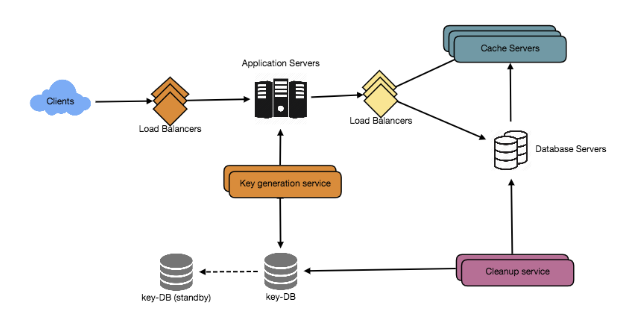

Components

- Mobile/Web based Clients : Users

- Load Balancers : To allocate requests to designated Application server using consistent hashing

- Application servers and Database servers

- NoSQL Database and replicas : Cassandra ( Key Value Store)

- Cache Server

Services

Key Generation service: To randomly generate 6 letters strings and store them into the database ( key — value). This will eliminate collision and duplications problems.

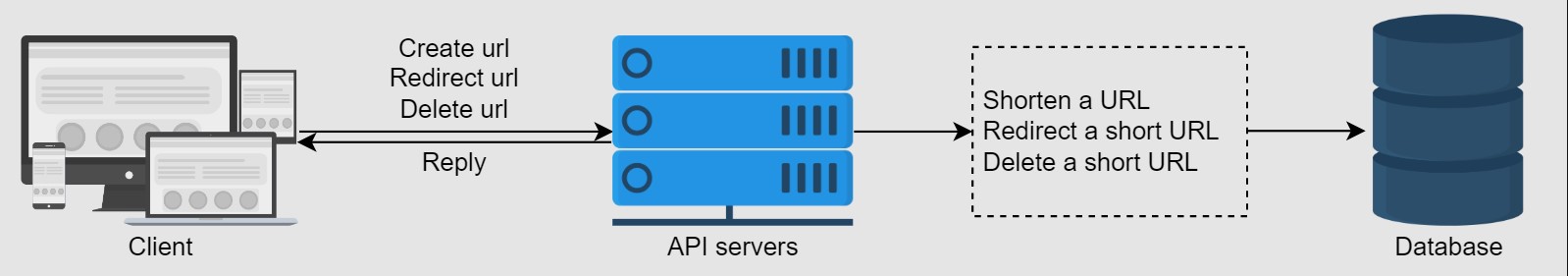

5. APIs Design

We need Rest APIs for the following features:

- Shrotening a URL

- Redirecting a short URL

- Deleting a shrot URL

5.1 Shortening a URL

We can create new short URLs with the following definition:

shortURL(api_dev_key, original_url, custom_alias=None, expiry_date=None)

The API call above has the following parameters:

Parameter Description

api_dev_key A registered user account’s unique identifier. This is useful in tracking a user’s activity and allows the system to control the associated services accordingly.

original_url The original long URL that is needed to be shortened.

custom_alias The optional key that the user defines as a customer short URL.

expiry_date The optional expiration date for the shortened URL.

A successful insertion returns the user the shortened URL. Otherwise, the system returns an appropriate error code to the user.

5.2 Redirecting a short URL

To redirect a short URL, the REST API’s definition will be:

redirectURL(api_dev_key, url_key)

With the following parameters:

Parameter Description

api_dev_key The registered user account’s unique identifier.

url_key The shortened URL against which we need to fetch the long URL from the database.

A successful redirection lands the user to the original URL associated with the url_key.

5.3 Deleting a short URL

Similarly, to delete a short URL, the REST API’s definition will be:

deleteURL(api_dev_key, url_key)

and the associated parameters will be:

Parameter Description

api_dev_key The registered user account’s unique identifier.

url_key The shortened URL against which we need to fetch the long URL from the database.

A successful deletion returns a system message, URL Removed, conveying the successful URL removal from the system.

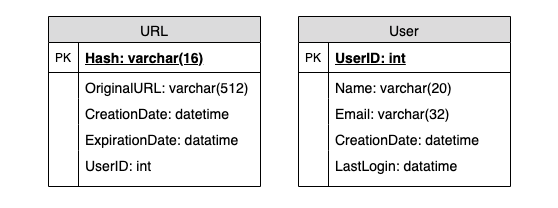

6. Database Design

A few observations about the nature of the data we will store:

- We need to store billions of records.

- Each object we store is small (less than 1K).

- There are no relationships between records—other than storing which user created a URL.

- Our service is read-heavy.

6.1 Database Schema

We would need two tables: one for storing information about the URL mappings, and one for the user’s data who created the short link.

Database: For services like URL shortening, there isn’t a lot of data to store. However, the storage has to be horizontally scalable. The type of data we need to store includes:

- User details.

- Mappings of the URLs, that is, the long URLs that are mapped onto short URLs. Our service doesn’t require user registration for the generation of a short URL, so we can skip adding certain data to our database. Additionally, the stored records will have no relationships among themselves other than linking the URL-creating user’s details, so we don’t need structured storage for record-keeping. Considering the reasons above and the fact that our system will be read-heavy, NoSQL is a suitable choice for storing data. In particular, MongoDB is a good choice for the following reasons:

- It uses leader-follower protocol, making it possible to use replicas for heavy reading.

- MongoDB ensures atomicity in concurrent write operations and avoids collisions by returning duplicate-key errors for record-duplication issues.

Question

Why are NoSQL databases like Cassandra or Riak not good choices instead of MongoDB?

Answer

Since our service is more read-intensive and less write-intensive, MongoDB suits our use case the best for the following reasons:

- NoSQL databases like Cassandra, Riak, and DynamoDB need read-repair during the reading stage and hence provide slower reads to write performance.

- They are leader-less NoSQL databases that provide weaker atomicity upon concurrent writes. Being a single leader database, MongoDB provides a higher read throughput as we can either read from the leader replica or follower replicas. The write operations have to pass through the leader replica. It ensures our system’s availability for reading-intensive tasks even in cases where the leader dies.

- Since Cassandra inherently ensures availability more than MongoDB, choosing MongoDB over Cassandra might make our system look less available. However, the time taken by the leader election algorithm is negligible compared to the time elapsed between short URL generation and its first usage, so it doesn’t hamper our system’s availability.

7. Basic System Design and Algorithm

Short URL generator: Our short URL generator will comprise a building block and an additional component:

- A sequencer to generate unique IDs

- A Base-58 encoder to enhance the readability of the short URL We built a sequencer in our building blocks section to generate 64-bit unique numeric IDs. However, our proposed design requires 64-bit alphanumeric short URLs in base-58. To convert the numeric (base-10) IDs to alphanumeric (base-58), we’ll need a base-10 for the base-58 encoder. We’ll explore the rationale behind these decisions alongside the internal working of the base-58 encoder in the next lesson.

7.1 Clarification

- How does encoding improve the readability of the short URL?

- How are the sequencer and the base-58 encoder in the short URL generation related?

7.2 Why to use encoding

Our sequencer generates a 64-bit ID in base-10, which can be converted to a base-64 short URL. Base-64 is the most common encoding for alphanumeric strings’ generation. However, there are some inherent issues with sticking to the base-64 for this design problem: the generated short URL might have readability issues because of look-alike characters. Characters like O (capital o) and 0 (zero), I (capital I), and l (lower case L) can be confused while characters like + and / should be avoided because of other system-dependent encodings.

So, we slash out the six characters and use base-58 instead of base-64 (includes A-Z, a-z, 0-9, + and /) for enhanced readability purposes. Let’s look at our base-58 definition.

Base-58

Value Character Value Character Value Character Value Character

0 1 15 G 30 X 45 n

1 2 16 H 31 Y 46 o

2 3 17 J 32 Z 47 p

3 4 18 K 33 a 48 q

4 5 19 L 34 b 49 r

5 6 20 M 35 c 50 s

6 7 21 N 36 d 51 t

7 8 22 P 37 e 52 u

8 9 23 Q 38 f 53 v

9 A 24 R 39 g 54 w

10 B 25 S 40 h 55 x

11 C 26 T 41 i 56 y

12 D 27 U 42 j 57 z

13 E 28 V 43 k

14 F 29 W 44 m

The highlighted cells contain the succeeding characters of the omitted ones: 0, O, I, and l.

7.3 Converting base-10 to base-58

Since we’re converting base-10 numeric IDs to base-58 alphanumeric IDs, explaining the conversion process will be helpful in grasping the underlying mechanism as well as the overall scope of the SUG. To achieve the above functionality, we use the modulus function.

Process: We keep diving the base-10 number by 58, making note of the remainder at each step. We stop where there is no remainder left. Then we assign the character indexes to the remainders, starting from assigning the recent-most remainder to the left-most place and the oldest remainder to the right-most place.

Example: Let’s assume that the selected unique ID is 2468135791013. The following steps show us the remainder calculations:

Base-10 = 2468135791013

2468135791013 % 58=17

42554065362 % 58=6

733690782 % 58=4

12649841 % 58=41

218100 % 58=20

3760 % 58=48

64 % 58=6

1 % 58=1 Now, we need to write the remainders in order of the most recent to the oldest order.

Base-58 = [1] [6] [48] [20] [41] [4] [6] [17]

Using the table above, we can write the associated characters with the remainders written above.

Base-58 = 27qMi57J

7.4 Converting base-58 to base-10

The decoding process holds equal importance as the encoding process, as we used a decoder in case of custom short URLs generation, as explained in the design lesson.

Process: The process of converting a base-58 number into a base-10 number is also straightforward. We just need to multiply each character index (value column from the table above) by the number of 58s that position holds, and add all the individual multiplication results.

Example: Let’s reverse engineer the example above to see how decoding works.

Base-58: 27qMi57J

2_{58} = 1 x 58^{7} = 2207984167552

7_{58} = 6 x 58^{6} = 228412155264

q_{58} = 48 x 58^{5} = 31505124864

M_{58} = 20 x 58^{4} = 226329920

i_{58} = 41 \times 58^{3} = 7999592

5_{58} = 4 \times 58^{2} = 13456

7_{58} = 6 \times 58^{1} = 348

J_{58} = 17 \times 58^{0} = 17

Base-10 = 17 + 348 + 13456 + 7999592 + 226329920 + 31505124864 + 228412155264 + 2207984167552

Base-10 = 2468135791013.

This is the same unique ID of base-10 from the previous example.

7.5 The scope of the short URL generator

-

The short URL generator is the backbone of our URL shortening service. The output of this short URL generator depends on the design-imposed limitations, as given below:

-

The generated short URL should contain alphanumeric characters.

-

None of the characters should look alike.

-

The minimum default length of the generated short URL should be six characters. These limitations define the scope of our short URL generator. We can define the scope, as shown below:

- Starting range: Our sequencer can generate a 64-bit binary number that ranges from 1 to (2^{64}-1). To meet the requirement for the minimum length of a short URL, we can select the sequencer IDs to start from at least 10 digits, i.e., 1 Billion.

- Ending point: The maximum number of digits in sequencer IDs that map into the short URL generator’s output depends on the maximum utilization of 64 bits, that is, the largest base-10 number in 64-bits. We can estimate the total number of digits in any base by calculating these two points:

- The numbers of bits to represent one digit in a base-n. This is given by log_2{n}

- Number of digits = Total bits available/Number of bits to represent one digit

Let’s see the calculations above for both the base-10 and base-58 mathematically:

- Base-10:

- The number of bits needed to represent one decimal digit = log_2{10} = 3.13

- The total number of decimal digits in 64-bit numeric ID = 64 / 3.13= 20

Base-58: The number of bits needed to represent one decimal digit = log_2{58}=5.85 The total number of base-58 digits in a 64-bit numeric ID =64 / 5.85=11

Maximum digits: The calculations above show that the maximum digits in the sequencer generated ID will be 20 and consequently, the maximum number of characters in the encoded short URL will be 11.

Question 1

Since we’re using the 10 digits and beyond sequencer IDs, is there a way we can use the sequencer IDs shorter than 10 digits?

Answer

We can use the range below the ten digits sequencer IDs for custom short links for users with premium memberships. It will ensure two benefits:

Utilization of the blocked range of IDs

Less than six characters short URLs

Example: Let’s assume that the user requests abc as a custom short URL, and it’s available in our system, as there is no instance in the data store matching with this short URL. We need to perform the following two operations:

1. Assign this short URL to the requested long URL and store this record in the datastore.

2. Mark the associated unique ID unusable. To find the associated unique ID, we need to decode abc into base-10. Using the above decode method, we come up with the base-10 unique ID value as 113019. The unique ID is less than 1 Billion, as the custom short URL is less than six characters, conforming to the above-stated two benefits.

Our system doesn’t ensure a guaranteed custom short link generation, as some other premium member might have claimed the requested custom short URL.

Question 2

What should the short URL be for the sequencer’s largest number?

Hide Answer

Since the sequencer’s largest number is 18,446,744,073,709,551,615. That is, 2^{64}-1, the base-58 equivalent of it will be jpXCZedGfVQ, conforming to our calculations above.

7.6 The sequencer’s lifetime

The number of years that our sequencer can provide us with unique IDs depends on two factors:

- Total numbers available in the sequencer = 2^{64} - 10^{9} (starting from 1 Billion as discussed above)

- Number of requests per year = 200 Million per month×12=2.4 Billion (as assumed in Requirements) So, taking the above two factors into consideration, we can calculate the expected life of our sequencer. The lifetime of the sequencer = total numbers available/yearly requests ={2^{64}-10^{9}} / {2.4 Billion} = 7,686,143,363.63 years

The lifetime of the sequencer = total numbers available/yearly requests ={2^{64}-10^{9}} / {2.4 Billion} = 7,686,143,363.63 years

Life expectancy for sequencer

Number of requests per month 200 Million

Number of requests per year 2.4 Billion

Lifetime of sequencer 7,686,143,363.63 years

Other building blocks: Beside the elements mentioned above, we’ll also incorporate other building blocks like load balancers, cache, and rate limiters.

- Load balancing: We can employ Global Server Load Balancing (GSLB) apart from local load balancing to improve availability. Since we have plenty of time between a short URL being generated and subsequently accessed, we can safely assume that our DB is geographically consistent and that distributing requests globally won’t cause any issues.

- We can add a Load balancing layer at three places in our system:

- Between Clients and Application servers

- Between Application Servers and database servers

- Between Application Servers and Cache servers

- We can add a Load balancing layer at three places in our system:

- Cache: For our specific read-intensive design problem, Memcached is the best choice for a cache solution. We require a simple, horizontally scalable cache system with minimal data structure requirements. Moreover, we’ll have a data-center-specific caching layer to handle native requests. Having a global caching layer will result in higher latency.

- How much cache memory should we have? We can start with 20% of daily traffic and, based on clients’ usage pattern, we can adjust how many cache servers we need. As estimated above, we need 170GB memory to cache 20% of daily traffic. Since a modern-day server can have 256GB memory, we can easily fit all the cache into one machine. Alternatively, we can use a couple of smaller servers to store all these hot URLs.

- Which cache eviction policy would best fit our needs? When the cache is full, and we want to replace a link with a newer/hotter URL, how would we choose? Least Recently Used (LRU) can be a reasonable policy for our system. Under this policy, we discard the least recently used URL first. We can use a Linked Hash Map or a similar data structure to store our URLs and Hashes, which will also keep track of the URLs that have been accessed recently.

- How can each cache replica be updated? Whenever there is a cache miss, our servers would be hitting a backend database. Whenever this happens, we can update the cache and pass the new entry to all the cache replicas. Each replica can update its cache by adding the new entry. If a replica already has that entry, it can simply ignore it.

- Rate limiter: Limiting each user’s quota is preferable for adding a security layer to our system. We can achieve this by uniquely identifying users through their unique api_dev_key and applying one of the discussed rate-limiting algorithms (see Rate Limiter from Building Blocks). Keeping in view the simplicity of our system and the requirements, the fixed window counter algorithm would serve the purpose, as we can assign a set number of shortening and redirection operations per api_dev_key for a specific timeframe.

Question 1

How will we maintain a unique mapping if redirection requests can go to different data centers that are geographically apart? Does our design assume that our DB is consistent geographically?

Answer

We initially assumed that our data center was globally consistent. Let’s look at the problem differently and consider the opposite case: we need to filter the redirection requests based on data centers.

Solution: An simple way of achieving this functionality is to introduce a unique character in the short URL. This special character will act as an indicator for the exact data center.

Example: Let’s assume that the short URL that needs redirection is service.com/x/short123/, where x indicates the data center containing this record.

In this solution, if the short URL goes to the wrong data center, it can be redirected to the correct one. However, if a specific data center is not reachable for a specific short URL (and that URL is not yet cached), the redirection will fail.

Question 2

How will the data-center-specific caching handle an unseen redirection request?

Answer

Since we’ve assumed the data-center-specific caching solution for our system, a case needs highlighting: handling unseen redirection requests by our system.

Scenario: The scenario entails receiving an unknown redirection request at a data center. Since the local cache wouldn’t have that entry, it would fetch that record from the globally consistent database and place this entry into the local cache for future use.

Question 3

What is the probability of collision when we ask the short URL generator for a new short URL?

Answer

We ask the sequencer for a unique ID and by the definition of our sequencer’s design, there will never be duplication in IDs. We then encode those IDs, which also ensures no duplication. Hence, the regular short URL generation process ensures no duplication in records.

Now let’s consider the case of custom short URLs. Since the user is providing the short URL, there can be a duplication. We can easily calculate the probability of this collision by taking into account the size of the database containing short URL records.

Let’s assume there are n already generated short URLs in the database. The probability that the user-provided custom short URL will be similar to an already existing one can be given by 1/n.

8. Data Partitioning and Replication

To scale out our DB, we need to partition it so that it can store information about billions of URLs. We need to come up with a partitioning scheme that would divide and store our data into different DB servers.

- Range Based Partitioning: We can store URLs in separate partitions based on the first letter of the hash key. Hence we save all the URLs starting with letter ‘A’ (and ‘a’) in one partition, save those that start with letter ‘B’ in another partition and so on. This approach is called range-based partitioning. We can even combine certain less frequently occurring letters into one database partition. We should come up with a static partitioning scheme so that we can always store/find a URL in a predictable manner.

The main problem with this approach is that it can lead to unbalanced DB servers. For example, we decide to put all URLs starting with letter ‘E’ into a DB partition, but later we realize that we have too many URLs that start with the letter ‘E’. - Hash-Based Partitioning: In this scheme, we take a hash of the object we are storing. We then calculate which partition to use based upon the hash. In our case, we can take the hash of the ‘key’ or the short link to determine the partition in which we store the data object.

Our hashing function will randomly distribute URLs into different partitions (e.g., our hashing function can always map any ‘key’ to a number between [1…256]), and this number would represent the partition in which we store our object.

9. Purging or DB cleanup

Should entries stick around forever or should they be purged? If a user-specified expiration time is reached, what should happen to the link?

If we chose to actively search for expired links to remove them, it would put a lot of pressure on our database. Instead, we can slowly remove expired links and do a lazy cleanup. Our service will make sure that only expired links will be deleted, although some expired links can live longer but will never be returned to users.

- Whenever a user tries to access an expired link, we can delete the link and return an error to the user.

- A separate Cleanup service can run periodically to remove expired links from our storage and cache. This service should be very lightweight and can be scheduled to run only when the user traffic is expected to be low.

- We can have a default expiration time for each link (e.g., two years).

- After removing an expired link, we can put the key back in the key-DB to be reused.

- Should we remove links that haven’t been visited in some length of time, say six months? This could be tricky. Since storage is getting cheap, we can decide to keep links forever.

9. Security and Permissions

Question

Can users create private URLs or allow a particular set of users to access a URL?

Answer

We can store the permission level (public/private) with each URL in the database. We can also create a separate table to store UserIDs that have permission to see a specific URL. If a user does not have permission and tries to access a URL, we can send an error (HTTP 401) back. Given that we are storing our data in a NoSQL wide-column database like Cassandra, the key for the table storing permissions would be the ‘Hash’ (or the KGS generated ‘key’). The columns will store the UserIDs of those users that have the permission to see the URL.

10. Design diagram

- Shortening: Each new request for short link computation gets forwarded to the short URL generator (SUG) by the application server. Upon successful generation of the short link, the system sends one copy back to the user and stores the record in the database for future use.

Question 1

How does our system avoid duplicate short URL generation?

Answer

- Computing a short URL for an already existing long URL is redundant, and the system sends the long URL to the database server to check its existence in the system. The system will check the respective entry in the cache first and then query the database.

- If the short URL for the corresponding long URL is already present, the database returns the saved short URL to the application server which reroutes the requested short URL to the user.

- If the requested short URL is unavailable in the system, the application server requests the SUG to compute the short URL for the requested long URL. Once computed, the SUG sends back a copy of the requested short URL to the application server and another copy to the database server.

Question 2

How do we ensure that two concurrent requests for a short URL do not overwrite?

Answer

Concurrency in handling URL shortening requests is essential, and we achieve it as follows:

MongoDB ensures consistency by locking and concurrency control protocols, preventing the users from modifying the same data simultaneously.

In MongoDB, all the write requests go through the single leader and hence exclude the possibility of race conditions due to the serialization of requests via a single leader.

- Redirection: Application servers, upon receiving the redirection requests, check the storage units (caching system and database) for the required record. If found, the application server redirects the user to the associated long URL.

Question

How does our system ensure that our data store will not be a bottleneck?

Hide Answer

We can ensure that our data store doesn’t become a bottleneck, using the following two approaches:

1. We use a range-based sequencer in our design, which ensures basic level mapping between the servers and the short URLs. We can redirect the request to the respective database for a quick search.

2. As discussed above, we can also have unique IDs for various data stores and integrate them into short URLs. We can subsequently redirect requests to the respective datastore for efficient request handling.

Both of these approaches ensure smooth traffic handling and mitigate the risk of the datastore becoming a bottleneck.

- Deletion: A logged-in user can delete a record by requesting the application server which forwards the user details and the associated URL’s information to the database server for deletion. A system-initiated deletion can also be triggered upon an expiry time, as we’ll see ahead.

- Custom short links: This task begins with checking the eligibility of the requested short URL. The maximum length allowed is 11 alphanumeric digits. We can find the details on the allowed format and the specific digits in the next lesson. Once verified, the system checks its availability in the database. If the requested URL is available, the user receives a successful short URL generation message, or an error message in the opposite case. The illustration below depicts how URL shortening, redirection, and deletion work.

Question

Upon successful allocation of a custom short URL, how does the system modify its records?

Answer

Since the custom short URL is the base-58 encoding of an available base-10 unique ID, marking that unique ID as unavailable for future use is necessary for the system’s integrity.

On the backend, the system accesses the server with the base-10 equivalent unique ID of that specific base-58 short URL. It marks the ID as unavailable in the range, eliminating any chance of reallocating the same ID to any other request.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: